Chinese Thought

子疾病,子路請禱。

子曰。有諸 。子路對曰。有之。誄曰:禱爾於上下神祗』

子曰。丘之禱久矣

― Analects 7:34

The above quote might be considered the essence of Chinese philosophy. Confucius (551–479 BCE) is seen here stating that living a good life is itself enough to serve as prayer and ritual. What we see as Chinese philosophy was the culmination of a large number of schools that emerged during the Warring States era, including Confucianism, Legalism, Agriculturalism, Mohism, Chinese Naturalism, School of Names (Logic), and Taoism (Liang-Hung & Yu-Ling, 2009). This became known as the Hundred Schools of Thought (諸子百家; zhūzǐ bǎijiā). These schools ranged from utopian proto-communalism (Agriculturalism) and being attuned to nature (Taoism) to support for government and state power (Confucianism). In many ways, Confucianism is responsible for the first meritocracy where status was seen as something that could be achieved through hard work and education rather than through birth into the aristocracy (Kung Fu Tze, 1998). Most of the other schools of thought were supressed by various Chinese dynasties and only Confucianism, Taoism, and later Buddhism became ascendent in Chinese society.

The central concept of all Chinese philosophy has been Tao or the correct way to live. This was interpreted by Confucius as living within regimented society, while Taoism saw this as an abstract concept lived through non-action (wu wei). The Indian concepts from Buddhism—which arrived in China during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE)—were added to this. This led to the translation of numerous Sanskrit texts into Classical Chinese, which then went on to influence Japanese and Korean culture.

Chinese philosophy and natural science continued to develop over the next two millennia. We can thank the Chinese philosophers for inventing gun powder, paper, printing, and the compass (called the Four Great Inventions, 四大发明). These inventions have perhaps had the greatest influence on world history. The introduction of paper into the Islamic world led to the writing down of the steps of mathematical proofs (Greek and Indian mathematicians usually gave the final proofs and not necessarily the steps they followed). Later on, the printing press and movable type would allow knowledge to spread among the masses and lead to even greater leaps in technology.

The Three Roots of Modern Philosophy

Now that you have learned about the three civilizations that gave birth to philosophy, see if you can reflect on what has been discussed and come up with some of the differences between them. Consider the following points in your reflection:

- The belief or lack thereof in the supernatural

- The emphasis on respecting ancient traditions

- The impetus to challenge pre-existing beliefs

Media Attributions

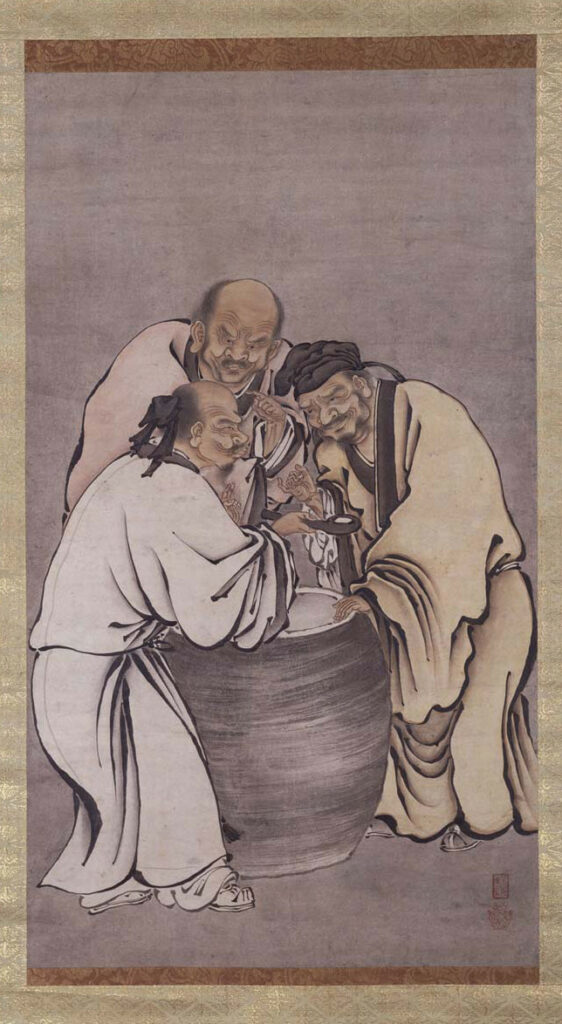

- Figure 1.8 The Three Vinegar Tasters (cropped) by a Kanō school artist during the Mromachi period [Photo from the Tokyo National Musuem], via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.