The Scientific Revolution

Descartes first wrote the words, “I think, therefore I am”, in his Discourse on the Method in 1637. What Descartes was trying to do with this simple phrase was actually much more ambitious than proving his own existence. He was trying to create a foundation for knowledge—a starting point upon which all future attempts at understanding and describing the world would depend. And, of course, to know anything requires a knower in the first place, right? In other words, we need a mind. Descartes recognized this, so he sought to found all knowledge on the existence of a thinker’s own mind.

To prove that his mind existed, Descartes did not actually start with the act of thinking. He started instead with the act of radical doubt: he doubted his knowledge of the external world, God, and even his own mind. The reason for this radical doubt was to ensure that he did not accept anything without justification. So, the first stop was to doubt every single belief he held.

For one thing, Descartes understood that sometimes our senses deceive us, so we must doubt everything we experience and observe. He further understood that even experts sometimes make simple mistakes, so we should doubt everything we have been taught. Lastly, Descartes suggested that even our thoughts might be complete fabrications—be they the products of a dream or the machinations of an evil demon—so we should also doubt that those thoughts themselves are correct.

Yet in the process of doubting everything, he realized that there was something that he could not doubt—the very act of doubting! Thus, Descartes could at least be certain that he was doubting. But doubting is itself a form of thinking. Therefore, Descartes could also be certain that he was thinking. But surely there can be no thinking without a thinker (i.e., a thinking mind). Hence, Descartes proved to himself the existence of his own mind: I doubt; therefore, I think; therefore, I am.

Importantly for Descartes, this argument is intuitively true, as anyone would agree that doubting is a way of thinking and that thinking requires a mind. Thus, according to Descartes, the existence of a doubter’s own mind is, for the doubter, established beyond any reasonable doubt.

It is important to notice what Descartes is claiming to exist through this line of reasoning. He is not suggesting that his physical body exists. So far, he has only proven to himself that his mind exists. If you think about it, the second “I” in “I think therefore I am” should really be “my mind”—hence, “I think, therefore my mind is”. Descartes and others started a cascade of thinking that promoted originality of thought and openness to new ideas. Scholars throughout Europe engaged with each other across the next few decades, improving upon the ideas they inherited from past civilizations. This led to the Age of Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution with Isaac Newton.

In 1687, Isaac Newton first published one of the most studied texts in the history and philosophy of science, Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (or the Principia for short). It is in this text that Newton first described the physical laws that are part and parcel of every first-year physics course, including his three laws of motion, his law of universal gravitation, and the laws of planetary motion. Of course, it would take several decades of debate and discussion for the community of the time to fully accept Newtonian physics. Nevertheless, by the 1760s, Newtonian cosmology and physics were accepted across Europe.

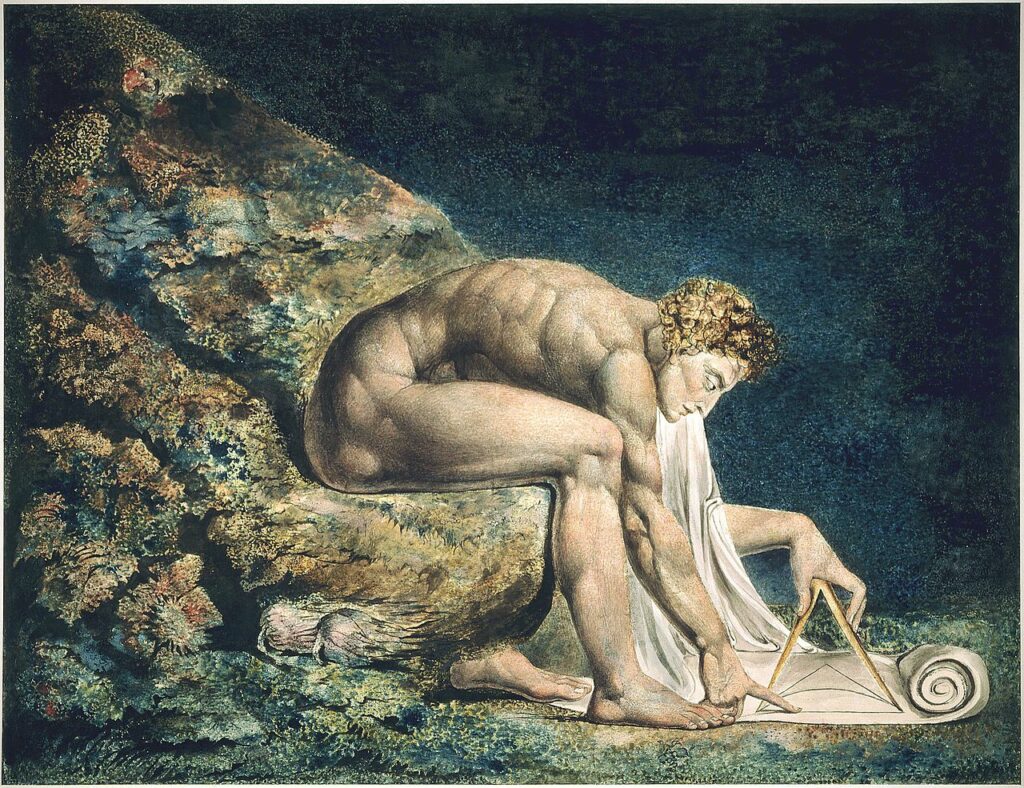

Keats lightheartedly said Newton “has destroyed all the poetry of the rainbow, by reducing it to the prismatic colours” (Haydon, 1929). Indeed, Romanticism became a movement that challenged the Enlightenment and tried to emphasize emotion over intellectualism while glorifying the medieval past. William Blake famously painted Newton as engaged in petty mathematics and ignoring the true beauty of nature. However, as Dawkins (1998) later stated, Newton did not destroy the beauty of nature. Rather, he allowed us to see it with renewed eyes. As we will see in the rest of this book, science allows us to appreciate nature on many different levels and from a more nuanced perspective.

Media Attributions

- Figure 1.11 Newton-WilliamBlake, by William Blake (1757–1827) [Photo from The William Blake Archive], via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.