Indian Thought

को अद्धा वेद क इह प्र वोचत्कुत आजाता कुत इयं विसृष्टिः

अर्वाग्देवा अस्य विसर्जनेनाथा को वेद यत आबभूव

इयं विसृष्टिर्यत आबभूव यदि वा दधे यदि वा न

यो अस्याध्यक्षः परमे व्योमन्त्सो अङ्ग वेद यदि वा न वेद

But then, who really knows and who can here proclaim it? Whence comes this world and how was it created?

Surely the gods came after creation.

So, who really know whence it arose?

Where did creation originate? Maybe there is a creator who fashioned it, and maybe he did not.

The ultimate creator who sees from the highest heaven, maybe he knows

– or maybe he knows now.

― Nasadiya Sukta, Rigveda (10:129)

The above verse from the Hindu sacred text Rig Veda shows the early blossoms of critical inquiry on the subcontinent. The author is not simply describing the creation of the universe as a story but actively questioning the very idea of whether it was created or not. Not only that, he is even questioning whether a creator exists or whether that creator knows about creation. This kind of questioning and challenging of tradition led to a cascade of philosophical texts around 500 BCE. Numerous schools of thought emerged with their own ideas about reality and how to understand it. Some of these were absorbed into mainstream religion, which evolved into what we now call Hinduism. Overall, there were six schools of orthodox or theistic inquiry and several heterodox schools that rivalled them (Doniger, 2014; Perrett, 2000).

Orthodox/Theistic Schools of Thought

| School of Thought | Important Scholar(s) | Tenants |

|---|---|---|

| Nyaya | Gautama, Udayana | The Indian school of logic. |

| Vaisheshika | Kaṇāda, Candra | Examined the universe in terms its smallest constituents: atoms. Accepted only direct observation and inference as the means of knowledge. |

| Samkhya | Kapila, Pancasikha | Postulated that all matter was made up of three gunas or qualities: sattva, rajas, and tamas |

| Yoga | Patanjali | The universe was thought to be dualistic: made of purusha (consciousness) and pratkrti (matter). Salvation could be achieved through meditative practices. |

| Mīmāmsa | Jaimini | Based on interpreting the meaning of sacred scriptures and rituals. |

| Vedanta | Baudhayana, Adi Sankara, Ramanuja, Madhva | A collection of different philosophies that postulates a supreme consciousness as the ultimate reality. The ability to know and experience it is thought be salvation. |

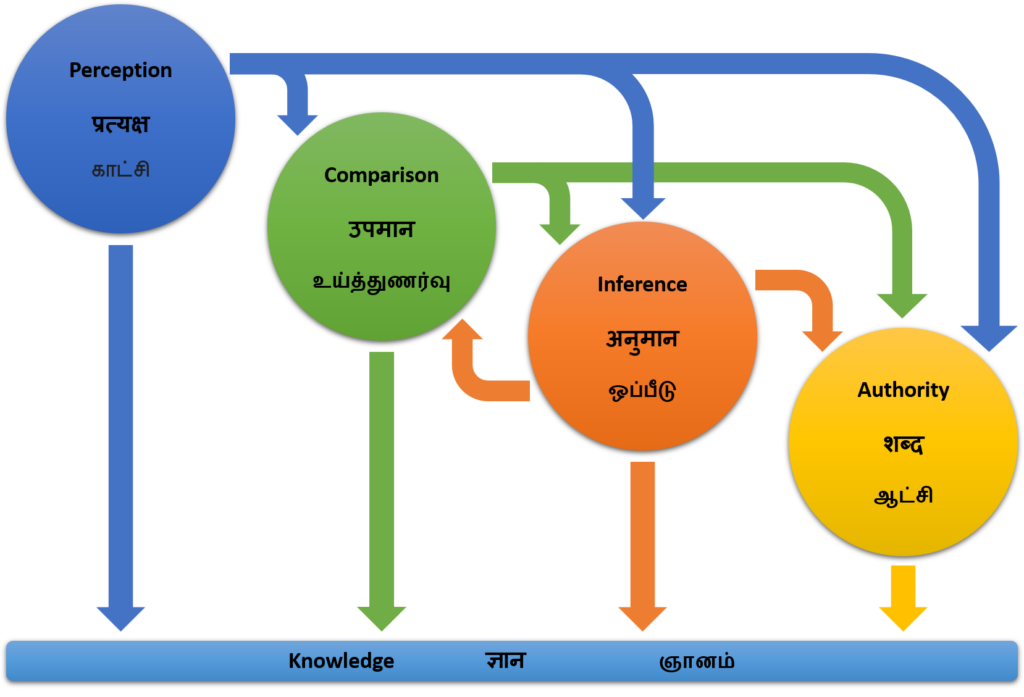

These six schools of philosophy continued to engage with each other for two millennia as they evolved different ideas about reality. Nyaya, or logic, became an important component in all schools of thought. Indian ideas about knowledge accepted six means of knowledge (प्रमाण, Pramāṇa). These were Pratyakṣa (perception), Anumāṇa (inference), Upamāṇa (analogy), Śabda (authority or the testimony of experts), Arthāpatti (postulation from circumstances), and Anupalabdhi (non-perception). Of these, direct perception was thought to be both external (from the senses) and internal (cognition). For example, seeing something burning is direct observation. Inference would be an indirect method of knowledge (e.g., seeing smoke and inferring that something is burning). Upamana, or analogy, would be where an example is given as a comparison (e.g., A zebra is an animal that looks almost like a cross between a horse and a donkey). Śabda means reliable authority, which could include accepted scripture or experts. Arthapatti, or postulation, means that you infer something from the context. For example, we can calculate the occurrence of eclipses based on the circumstances of where the sun, moon and Earth were during past eclipses. Anupalabdhi, or non-perception, means deriving proof through the non-perception of a thing (e.g., I do not see fire, so there must be nothing on fire). Of these six, the latter two were sometimes rejected by some scholars as inefficient means of knowledge (Flood, 1996).

Indian philosophers used numerous means of understanding the universe. For example, consider the following argument from the Vaisheshika school.

The Nature of Matter

If you keep cutting something into smaller and smaller pieces, could you keep on doing so continuously or is there a limit beyond which you could not go? This cannot be done through experiments as we cannot see beyond a certain limit.

Assume that matter is continuous. In this case, if you keep cutting a stone into smaller and smaller particles, you would end up with an infinite number of particles (since matter is continuous). Now, the Himalayan Mountain range could also be cut into smaller and smaller particles and you would end up with an infinite number. So, logically, you can start with a stone and end up with the same number of particles as the Himalayas which is ridiculous. Therefore, the original assumption that matter is continuous must be wrong and matter must be made up of a finite number of paramāṇus (atoms).

The atoms (or paramāṇus) in this case were not the atoms as we know them now. Indian philosophers thought these atoms were for the four elements: earth, air, fire, and water. However, we see that they were deriving these conclusions from logical thinking and not scriptural authority.

Indian schools of logic developed a strong tradition of critical analysis in debating various issues. Indian jurisprudence, for example, used the concept of purva paksha (former argument), referred to as the complaint, with other parts of a trial consisting of the pttara paksha (the response), kriyā (trial or investigation), and nirnaya (decision). The same was true of critical arguments in Indian texts where the purva paksha shows that the author has a deep familiarity with the thesis that he or she is criticizing. Only then are you allowed to state your own position vis-à-vis the former thesis. Philosophers who exemplified this technique include Adi Shankara (sixth century CE), Udyotakara (Nyāyavārttika, sixth to seventh century), Vācaspati Miśra (Tatparyatika, ninth century), Ramanujacharya (nonth century), Udayanacharya (Tātparyaparishuddhi, 10th century), Jayanta Bhatta (Nyāyamanjari, ninth century), Madhvacharya (13th century), Visvanatha (Nyāyasūtravṛtti, 17th century), Rādhāmohana Gosvāmī (Nyāyasūtravivarana, 18th century), and Kumaran Asan (1873–1924).

Heterodox Schools of Thought

In addition to the six orthodox schools of thought, there were numerous schools that challenged them. These were often called Nastika or non-theistic schools.

| School of thought | Important scholar(s) | Tenants |

|---|---|---|

| Buddhism | Gautama Buddha | Existence is suffering and one can escape the cycle of rebirth by practicing the eightfold path. |

| Jainism | Mahavira | Similar to Buddhism but advocates extreme nonviolence and austerities as a means of salvation. |

| Ājīvika | Makkhali Gosala | Postulates that each life is like a pre-woven thread that unfolds as fated. |

| Charvaka / Lokayata | Brihaspati, Ajita Kesakambalī | Atheism or materialism. Stated that with death all is annihilated so one must live happily. |

| Ajñana | Sañjaya Belaṭṭhiputta | Agnosticism |

| Akiriyāvāda | Pūraṇa Kassapa | Denied that there was any good or evil or that there were rewards or punishments for actions. |

| Sassatavāda | Pakudha Kaccāyana | Matter and souls are eternal and do not interact. |

The above table is a highly simplified description of rather complex ideas. However, it gives you an understanding of the diversity of thought. They challenged traditions about the afterlife and the existence of gods. Take for example the following verse:

इह-लोकात् परो नान्यः

स्वर्गोऽस्ति नरको न वा

शिव-लोकादयो मूढैः

कल्प्यन्तेऽन्यैः प्रतारकैः

There is no world other than this;

There is no heaven and no hell;

The realm of Shiva and like regions,

are fabricated by stupid imposters.

— Sarva-siddhanta Sangraha (2:8)

This statement by atheists in Ancient India would have been unthinkable in most of the ancient world. Indeed, it could get people killed in some parts of the world today! Even the teachers of these schools exhorted the need for critical thinking as can be seen in the following statement by the Buddha:

So, in this case, Kalamas, don’t go by reports, by legends, by traditions, by scripture, by logical conjecture, by inference, by analogies, by agreement through pondering views, by probability, or by the thought, ‘This contemplative is our teacher.’

When you know for yourselves that, ‘These qualities are unskilful; these qualities are blameworthy; these qualities are criticized by the wise; these qualities, when adopted & carried out, lead to harm & to suffering’ — then you should abandon them.

(Translated from Pali by Thanissaro Bhikkhu)

Such reasoning and the advocacy for it was the hallmark of critical thinking in India and continued for centuries. It allowed philosophers to explore new ideas. For example, Aryabhata (a mathematician from 476–550 CE) challenged the idea of a flat earth and calculated its circumference. His ideas were extrapolated upon by later mathematicians such as Bhaskara I (c. 600 CE) and Nilakantha Somayaji (1465 CE).

Media Attributions

- Figure 1.7 Created by the author