Critical Thinking

| तर्कोऽप्रतिष्ठः श्रुतयो विभिन्ना नैको ऋषिर्यस्य मतं प्रमाणम्।

धर्मस्य तत्त्वं निहितं गुहायाम् महाजनो येन गतः सः पन्थाः॥ |

Logic alone is insufficient. Neither revealed texts nor the holy seers can guide you. It is as if the true nature of dharma is hidden within a cave. The path may only be discerned by following the advice of great people. |

| —Mahabharata 3:314 |

Rational, objective thinking is a hallmark of science. Scientists need to be able to critically think about a problem or issue from a variety of perspectives, but it is not just scientists who need to be good thinkers. Critical thinking skills allow you to be a good consumer of ideas. Before deciding to buy a car, most people would spend some time evaluating what they wanted to buy, how much money they have to spend, what kind of car has a good safety record, and so on. The same thinking processes can be applied to ideas. These critical thinking processes are not necessarily intuitive. The good thing is that we can be taught what they are and how to use them. Thus, learning to think critically is a skill we can acquire with practise. Wade (1995) outlined eight processes that are used in critical thinking:

- Ask questions and be willing to wonder.

Curiosity precedes all scientific discoveries and is the basis for acquiring knowledge. For example, suppose you are interested in whether physical exercise is important for mood. Questions you might be wondering about could include:

- Does getting exercise change your mood?

- Do people who work out daily feel happier than people who don’t get any exercise?

- Does the kind of exercise matter?

- How much exercise makes a difference?

- How do you measure mood anyway?

- Define the problem.

We need to think about exactly what we want to know about the connection between exercise and mood. There are many ways to define exercise: it might mean walking every day to some people or lifting weights or doing yoga to others. Similarly, some people might interpret mood to be something fairly fleeting, while other people might think mood refers to clinical depression. We need to define the issue or question we are interested in.

- Examine the evidence.

Empirical evidence is the kind of support that critical thinkers seek. While you may be aware that a friend or relative felt better when they started running every day, that kind of evidence is anecdotal—it relates to one person, and we do not know if it would apply to other people. To look for evidence, we should turn to properly conducted studies. In psychology, these are most easily found in a searchable database called PsycINFO, which is available through university libraries. PsycINFO contains a vast index of all of the scholarly work published in psychology. Users can often download the original research articles straight from the PsycINFO website.

- Analyze assumptions and biases

Whenever we are reasoning about an idea, we are bound to begin with certain assumptions. For example, we might assume that exercise is good for mood because we usually assume that there is no downside to exercise. It helps if we can identify how we feel or think about an idea. All people are prone to some degree of confirmation bias—which is the tendency to look for evidence that supports your belief while, at the same time, discounting any that disproves it. This type of bias might be reflected in the social media accounts we follow—we follow people who think like us and do not follow people who might have opposing—yet possibly valid—points of view.

- Avoid emotional reasoning

This process is related to the previous one. It is hard to think about anything in a completely objective manner. Having a vested interest in an issue, or personal knowledge about it, often creates an emotional bias that we may not even be aware of. Feeling strongly about something does not make us think rationally; in fact, it can be a barrier to rational thinking. Consider any issue you feel strongly about. How easy is it to separate your emotions from your objectivity?

- Avoid oversimplification

Simplicity is comfortable, but it may not be accurate. We often strive for simple explanations for events because we do not have access to all of the information we need to fully understand the issue. This process relates to the need to ask questions. We should be asking ourselves “What do I not know about this issue?” Sometimes, issues are so complex that we can only address one little part. For example, many things are likely to affect mood; while we might be able to understand the connection to some types of physical exercise, we are not addressing any of the myriad of other social, cognitive, and biological factors that may be important.

- Consider other interpretations

Whenever you hear a news story telling you that something is good for you, it is wise to dig a little deeper. For example, many news stories report on research concerning the effects of alcohol. They may report that small amounts of alcohol have some positive health effects, that abstaining completely from alcohol is not good for you, and so on. A critical thinker would want to know more about how those studies were done, and they might suggest that perhaps moderate social drinkers differ from abstainers in a variety of lifestyle habits. Perhaps there are other interpretations for the link between alcohol consumption and health.

- Tolerate uncertainty

Uncertainty is uncomfortable. We want to know why things happen for good reasons. We are always trying to make sense of the world, and we look for explanations. However, sometimes, things are complicated and uncertain, or we do not have an explanation for it yet. Sometimes, we just have to accept that we do not have a full picture of why something happens or what causes what yet. We need to remain open to more information. It is helpful to be able to point out what we do not know, as well as what we do.

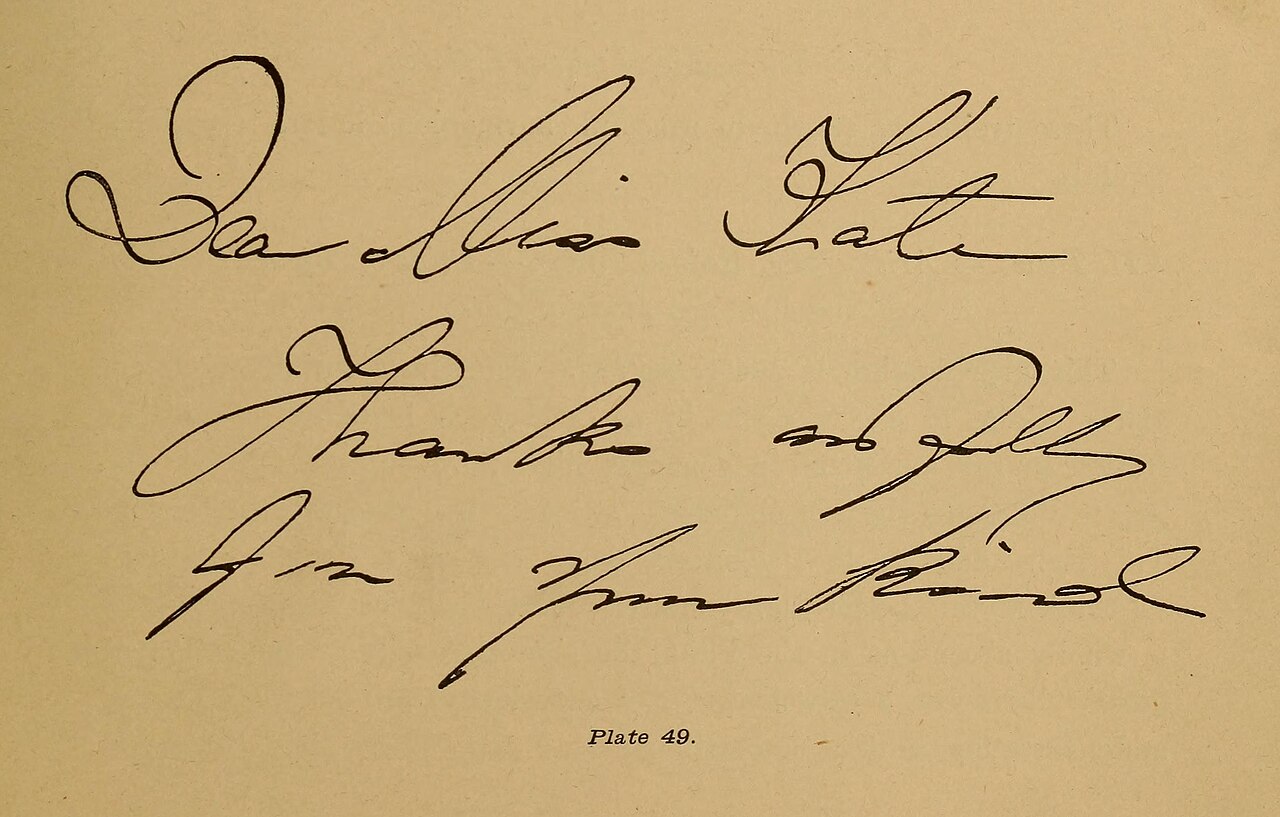

Pseudoscience Alert: Your Handwriting Does Not Reveal Your Character

One of the common beliefs that people have about personality is that it is revealed in one’s handwriting. Graphology is a pseudoscience that purports to show that aspects of our handwriting reflect aspects of our character. Reader’s Digest claims to explain the meaning of handwriting characteristics, such as spacing, size of characters, and how you cross your t’s (LaBianca & Gibson, n.d.). “If you dot your i’s high on the page, you likely have an active imagination, according to handwriting analysis experts. A closely dotted i is the mark of an organized and detail-oriented mind. If you dot your i’s to the left, you might be a procrastinator, and if you dot your i’s with a circle, you likely have playful and childlike qualities” (LaBianca & Gibson, n.d., “How do you dot your i’s?”).

Graphology has a long history (e.g., Münsterberg, 1915; Downey, 1919) and is related to many other attempts to explain people’s character based on aspects of physical appearance, such as the shape of one’s face, size of one’s hands, or bumps on one’s head (i.e., phrenology). People have always been interested in personality and how to measure, describe, and explain it.

Unfortunately, this attempt to understand people’s personality or career prospects by reading their handwriting has no empirical evidence to support it (Dazzi & Pedrabissi, 2009; Lilienfeld et al., 2010). Even though graphology was debunked several decades ago, the Reader’s Digest article on their website in 2020 shows that the belief persists.