The Scientific Method

An Abstract from the Journal: Psychological Science

Taking notes on laptops rather than in longhand is increasingly common. Many researchers have suggested that laptop note taking is less effective than longhand note taking for learning. Prior studies have primarily focused on students’ capacity for multitasking and distraction when using laptops. The present research suggests that even when laptops are used solely to take notes, they may still be impairing learning because their use results in shallower processing. In three studies, we found that students who took notes on laptops performed worse on conceptual questions than students who took notes longhand. We show that whereas taking more notes can be beneficial, laptop note takers’ tendency to transcribe lectures verbatim rather than processing information and reframing it in their own words is detrimental to learning. (Mueler & Oppenheimer, 2014, p. 1159)

In this abstract, the researcher has identified a research question—about the effect of taking notes on a laptop on learning—and identified why it is worthy of investigation—because the practice is ubiquitous and may be harmful to learning.

In this chapter, we will have a broad overview of the various stages of the research process. These include finding a topic of investigation, reviewing the literature, refining your research question and generating a hypothesis, designing and conducting a study, analyzing the data, coming to conclusions, and reporting the results.

A Model of Scientific Research

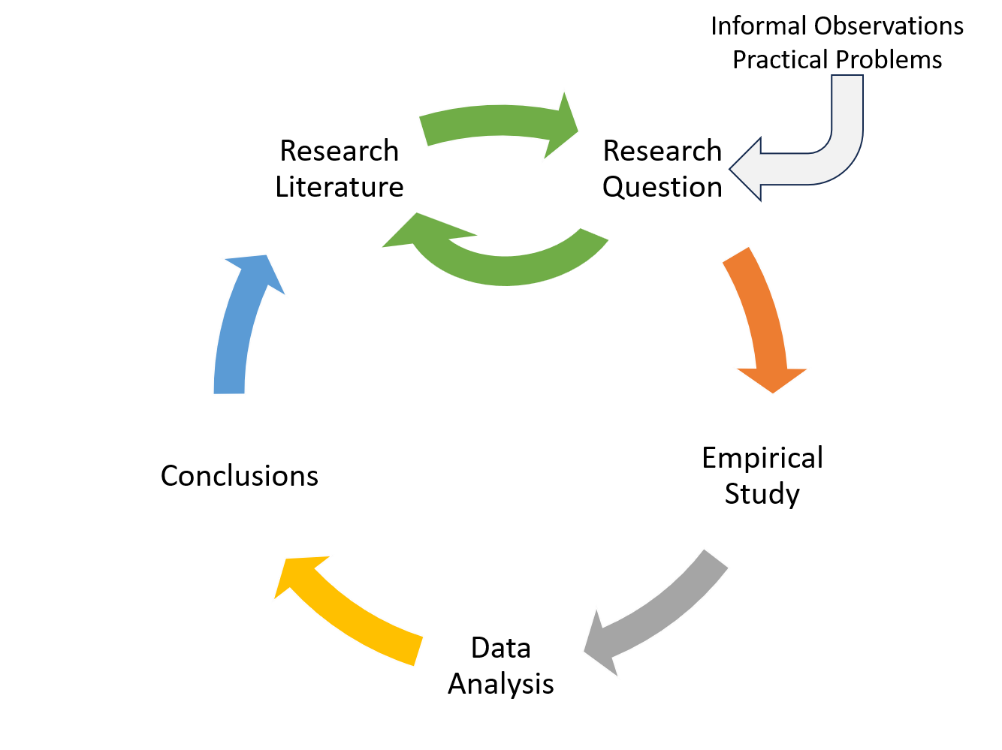

Figure 5.1 presents a simple model of scientific research. The researchers formulate a research question, conduct an empirical study designed to answer the question, analyze the resulting data, draw conclusions about the answer to the question, and publish the results so that they become part of the research literature (i.e., all the published research in that field). Because the research literature is one of the primary sources of new research questions, this process can be thought of as a cycle. New research leads to new questions, which lead to new research, and so on. Figure 3.1 also indicates that research questions can originate outside of this cycle either with informal observations or with practical problems that need to be solved. But even in these cases, the researcher would start by checking the research literature to see if the question had already been answered and refining it based on what previous research had already found.

A study by Mehl et al. (2007) is described nicely by this model. Their research question—whether women are more talkative than men—was suggested to them both by people’s stereotypes and by claims published in the research literature about the relative talkativeness of women and men. When they checked the research literature, however, they found that this question had not been adequately addressed in scientific studies. They then conducted a careful empirical study, analyzed the results (finding very little difference between women and men), formed their conclusions, and published their work so that it became part of the research literature. The publication of their article is not the end of the story, however, because their work suggests many new questions (about the reliability of the result, about potential cultural differences, etc.) that will likely be taken up by them and by other researchers inspired by their work.

As another example, consider that as cell phones became more widespread during the 1990s, people began to wonder whether, and to what extent, cell phone use had a negative effect on driving. Many psychologists decided to tackle this question scientifically (e.g., Collet et al., 2010). It was clear from previously published research that engaging in a simple verbal task impairs performance on a perceptual or motor task carried out at the same time, but no one had studied the effect specifically of cell phone use on driving. Under carefully controlled conditions, these researchers compared people’s driving performance while using a cell phone with their performance while not using a cell phone, both in the lab and on the road. They found that people’s ability to detect road hazards, reaction time, and maintain control of the vehicle were all impaired by cell phone use. Each new study was published and became part of the growing research literature on this topic. For instance, other research teams subsequently demonstrated that cell phone conversations carry a greater risk than conversations with a passenger who is aware of driving conditions, which often become a point of conversation (e.g., Drews et al., 2004).

Theories and Hypotheses

Before describing how to develop a hypothesis, it is important to distinguish between a theory and a hypothesis. A theory is a coherent explanation or interpretation of one or more phenomena. Although theories can take a variety of forms, one thing they have in common is that they go beyond the phenomena they explain by including variables, structures, processes, functions, or organizing principles that have not been observed directly. Consider, for example, Zajonc’s (1965) theory of social facilitation and social inhibition. He proposed that being watched by others while performing a task creates a general state of physiological arousal, which increases the likelihood of the dominant (most likely) response. So, for highly practiced tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make correct responses, but for relatively unpractised tasks, being watched increases the tendency to make incorrect responses. Notice that this theory—which has come to be called drive theory—provides an explanation of both social facilitation and social inhibition that goes beyond the phenomena themselves by including concepts such as “arousal” and “dominant response,” along with processes such as the effect of arousal on the dominant response.

Outside of science, referring to an idea as a theory often implies that it is untested—perhaps no more than a wild guess. In science, however, the term “theory” has no such implication. A theory is simply an explanation or interpretation of a set of phenomena. It can be untested, but it can also be extensively tested, well-supported, and accepted as an accurate description of the world by the scientific community. The theory of evolution by natural selection, for example, is a theory because it is an explanation of the diversity of life on earth—not because it is untested or unsupported by scientific research. On the contrary, the evidence for this theory is overwhelmingly positive and nearly all scientists accept its basic assumptions as accurate. Similarly, the “germ theory” of disease is a theory because it is an explanation of the origin of various diseases, not because there is any doubt that many diseases are caused by microorganisms that infect the body.

A hypothesis, on the other hand, is a specific prediction about a new phenomenon that should be observed if a particular theory is accurate. It is an explanation that relies on just a few key concepts. Hypotheses are often specific predictions about what will happen in a particular study. They are developed by considering existing evidence and using reasoning to infer what will happen in the specific context of interest. Hypotheses are often but not always derived from theories. So, a hypothesis is often a prediction based on a theory, but some hypotheses are a-theoretical; only after a set of observations have been made is a theory developed. This is because theories are broad in nature and explain larger bodies of data. So, if our research question is really original, then we may need to collect some data and make some observations before we can develop a broader theory.

Theories and hypotheses always have this if-then relationship. “If drive theory is correct, then cockroaches should run through a straight runway faster, and a branching runway more slowly, when other cockroaches are present.” Although hypotheses are usually expressed as statements, they can always be rephrased as questions. “Do cockroaches run through a straight runway faster when other cockroaches are present?” Thus, deriving hypotheses from theories is an excellent way of generating interesting research questions.

But how do researchers derive hypotheses from theories? One way is to generate a research question using the techniques discussed in this chapter and then ask whether any theory implies an answer to that question. For example, you might wonder whether expressive writing about positive experiences improves health as much as expressive writing about traumatic experiences. Although this question is an interesting one on its own, you might then ask whether the habituation theory—the idea that expressive writing causes people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings—implies an answer. In this case, it seems clear that if the habituation theory is correct, then expressive writing about positive experiences should not be effective because it would not cause people to habituate to negative thoughts and feelings. A second way to derive hypotheses from theories is to focus on some component of the theory that has not yet been directly observed. For example, a researcher could focus on the process of habituation—perhaps hypothesizing that people should show fewer signs of emotional distress with each new writing session.

Among the very best hypotheses are those that distinguish between competing theories. For example, Norbert Schwarz and his colleagues considered two theories of how people make judgments about themselves, such as how assertive they are (Schwarz et al., 1991). Both theories held that such judgments are based on relevant examples that people bring to mind. However, one theory was that people base their judgments on the number of examples they bring to mind, and the other was that people base their judgments on how easily they bring those examples to mind. To test these theories, the researchers asked people to recall either six times when they were assertive (which is easy for most people) or 12 times (which is difficult for most people). Then, they asked them to judge their own assertiveness. Note that the number-of-examples theory implies that people who recalled 12 examples should judge themselves to be more assertive because they recalled more examples, but the ease-of-examples theory implies that participants who recalled six examples should judge themselves as more assertive because recalling the examples was easier. Thus, the two theories made opposite predictions so that only one of the predictions could be confirmed. The surprising result was that participants who recalled fewer examples judged themselves to be more assertive—providing particularly convincing evidence in favor of the ease-of-retrieval theory over the number-of-examples theory.

Theory Testing

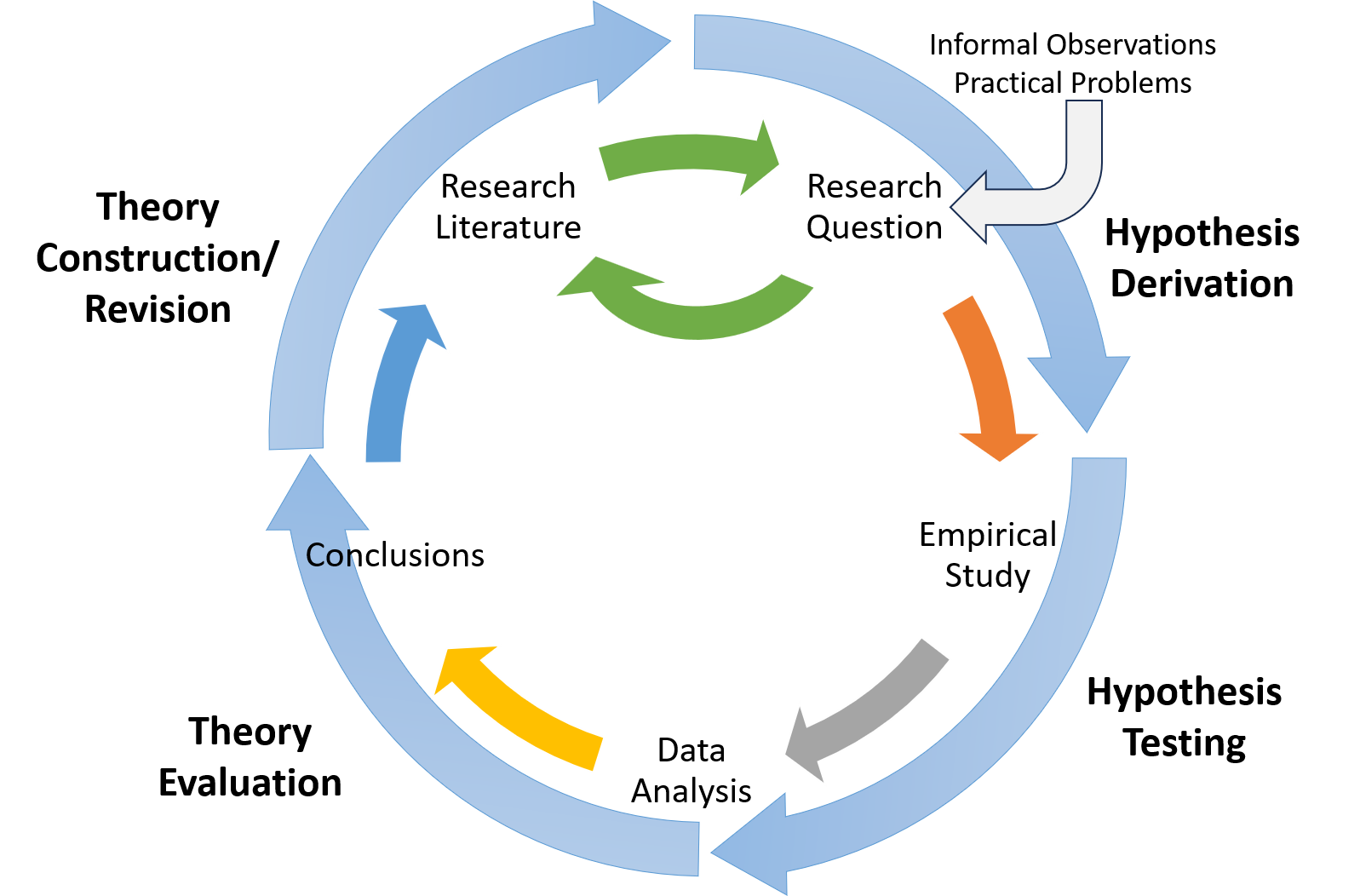

The primary way that scientific researchers use theories is sometimes called the hypothetico-deductive method (although this term is much more likely to be used by philosophers of science than by scientists themselves). Researchers begin with a set of phenomena and either construct a theory to explain or interpret them or choose an existing theory to work with. They then make a prediction about some new phenomenon that should be observed if the theory is correct. Again, this prediction is called a hypothesis. The researchers then conduct an empirical study to test the hypothesis. Finally, they re-evaluate the theory in light of the new results and revise it if necessary.

This process is usually conceptualized as a cycle because the researchers can then derive a new hypothesis from the revised theory, conduct a new empirical study to test the hypothesis, and so on. As Figure 5.2 shows, this approach meshes nicely with the model of scientific research in psychology presented earlier in the textbook—creating a more detailed model of “theoretically motivated” or “theory-driven” research.

As an example, let us consider Zajonc’s (1965) research on social facilitation and inhibition. He started with a somewhat contradictory pattern of results from the research literature. He then constructed his drive theory, according to which being watched by others while performing a task causes physiological arousal, which increases an organism’s tendency to make the dominant response. This theory predicts social facilitation for well-learned tasks and social inhibition for poorly learned tasks. He now had a theory that organized previous results in a meaningful way—but he still needed to test it. He hypothesized that if his theory was correct, he should observe that the presence of others improves performance in a simple laboratory task but inhibits performance in a difficult version of the very same laboratory task.

To test this hypothesis, one of the studies he conducted used cockroaches as subjects (Zajonc et al., 1969). The cockroaches ran either down a straight runway (an easy task for a cockroach) or through a cross-shaped maze (a difficult task for a cockroach) to escape into a dark chamber when a light was shined on them. They did this either while alone or in the presence of other cockroaches in clear plastic “audience boxes.” Zajonc found that cockroaches in the straight runway reached their goal more quickly in the presence of other cockroaches, but cockroaches in the cross-shaped maze reached their goal more slowly when they were in the presence of other cockroaches. Thus, he confirmed his hypothesis and provided support for his drive theory. (Zajonc also showed that drive theory existed in humans [Zajonc & Sales, 1966] in many other studies afterward).

Incorporating Theory into Your Research

When you write your research report or plan your presentation, be aware that there are two basic ways that researchers usually include theories. The first is to raise a research question, answer that question by conducting a new study, and then offer one or more theories (usually more) to explain or interpret the results. This format works well for applied research questions and for research questions that existing theories do not address. The second way is to describe one or more existing theories, derive a hypothesis from one of those theories, test the hypothesis in a new study, and finally reevaluate the theory. This format works well when there is an existing theory that addresses the research question—especially if the resulting hypothesis is surprising or conflicts with a hypothesis derived from a different theory.

Using theories in your research will not only give you guidance in coming up with experiment ideas and possible projects, but it will also lend legitimacy to your work. Psychologists have been interested in a variety of human behaviours and have developed many theories along the way. Using established theories will help you break new ground as a researcher, not limit you from developing your own ideas.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

There are three general characteristics of a good hypothesis.

First, a good hypothesis must be testable and falsifiable. We must be able to test the hypothesis using the methods of science, and if you recall Popper’s falsifiability criterion, it must be possible to gather evidence that will disconfirm the hypothesis if it is indeed false.

Second, a good hypothesis must be logical. As described above, hypotheses are more than just a random guess. Hypotheses should be informed by previous theories or observations and logical reasoning. Typically, we begin with a broad and general theory and use deductive reasoning to generate a more specific hypothesis to test based on that theory. Occasionally, however, when there is no theory to inform our hypothesis, we use inductive reasoning—which involves using specific observations or research findings—to form a more general hypothesis.

Finally, the hypothesis should be positive. That is, the hypothesis should make a positive statement about the existence of a relationship or effect, rather than a statement that a relationship or effect does not exist. As scientists, we do not set out to show that relationships do not exist or that effects do not occur, so our hypotheses should not be worded in a way to suggest that an effect or relationship does not exist. The nature of science is to assume that something does not exist and then seek to find evidence to prove this wrong to show that it really does exist. That may seem backward to you but that is the nature of the scientific method. The underlying reason for this is beyond the scope of this chapter but it has to do with statistical theory.

Media Attributions

- Figure 5.1 Jhangiani, R.S., Chiang, I.A. Cuttler, C. & Leighton, D.C. (2019). Research Methods in Psychology, Surrey, Canada: Kwantlen Polytechnic University.

- Figure 5.2 Jhangiani, R.S., Chiang, I.A. Cuttler, C. & Leighton, D.C. (2019). Research Methods in Psychology, Surrey, Canada: Kwantlen Polytechnic University.