A Renaissance in Thinking

Calvin says that he is certain, and [other sects] say that they are; Calvin says that they are wrong and wishes to judge them, and so do they. Who shall be judge? Who made Calvin the arbiter of all the sects, that he alone should kill? He has the Word of God and so have they. If the matter is certain, to whom is it so? To Calvin? But then why does he write so many books about manifest truth? . . . In view of the uncertainty we must define the heretic simply as one with whom we disagree. And if then we are going to kill heretics, the logical outcome will be a war of extermination, since each is sure of himself.

— Sebastian Castellio, Concerning Heretics: Whether They Are to Be Persecuted [quoted in Grayling (2007, pp. 53– 54)]

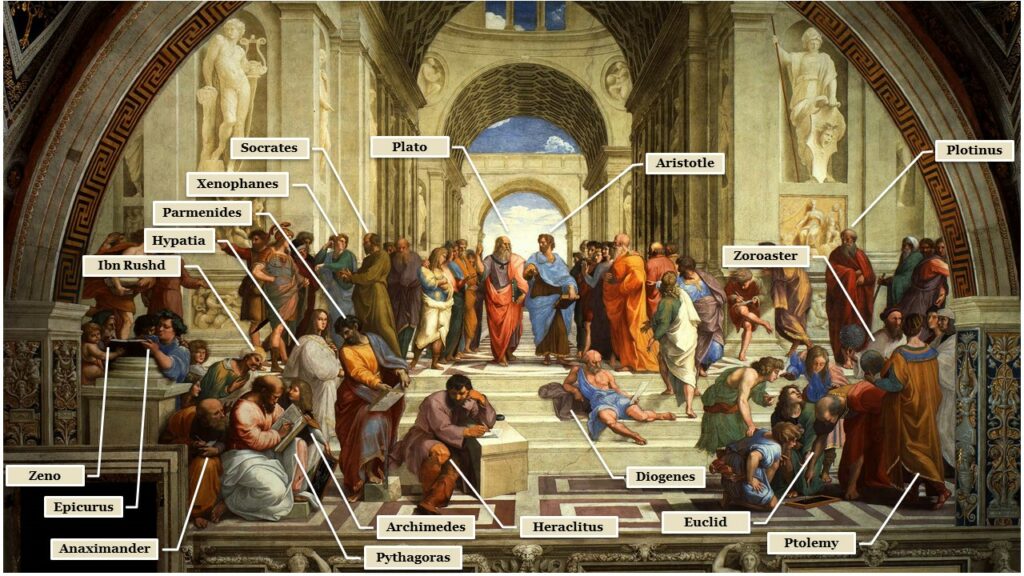

Where the Renaissance was the reawakening of the West to its ancient cultural and intellectual roots, the Scientific Revolution began as a critical response to ancient thinking and, in large part, that of Aristotle. This critical response was no quick refutation. Aristotle’s physics might now strike us as quite naïve and simplistic, but that is only because every contemporary middle school student gets a thorough indoctrination in Newton’s relatively recent way understanding of the physical world. The critical reaction to Aristotle that ignites the Scientific Revolution grew out of the tradition of painstakingly close study of Aristotle. The scholastic interpreters of Aristotle were not just wrongheaded folks stuck on the ideas of the past. They were setting the stage for new discoveries that could not have happened without their work. Again, our best critics are the ones who understand us the best and the one’s from whom we stand to learn the most. In the Scientific Revolution, we see a beautiful example of Socratic dialectic operating at the level of the traditions of scholarship.

Europe also experienced significant internal changes in the 16th century that paved the way for its intellectual reawakening. In response to assorted challenges to the authority of the Catholic Church and the decadence of 16th century Catholic churchmen, Martin Luther launched the Reformation. The primary tenet of the reformation was that faith concerns the individual’s relation to God who is knowable directly through the Bible without the intermediary of the Catholic Church. The Reformation and the many splintering branches of Protestant Christianity that it spawned undermined the dogmatic adherence to a specific belief system and opened the way for more free and open inquiry.

The undermining of Catholic orthodoxy brought on by the reformation combined with the rediscovery of ancient culture in the Renaissance jointly gave rise to the Scientific Revolution and what we often refer to as the Modern Classical period in philosophy. The reawakening of science and philosophy are arguably one and the same revolution. Developments in philosophy and science during this period are mutually informed, mutually influencing, and intermingled. Individuals including Newton, Leibniz, and Descartes are significant contributors to both science and philosophy.

Media Attributions

- Figure 1.10 Modified [cropped] image from “The School of Athens” [labeled] by Raphael (1483–1520), on Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.