Presenting Descriptive Statistics in Writing

Jessica/Feb 20: Images below are missing their license

Recall that APA style includes several rules for presenting numerical results in the text (see 4.31–4.34 in the APA (2020) Publication Manual). These include using words only for numbers less than 10 that do not represent precise statistical results and using numerals for numbers 10 and higher. However, statistical results are always presented in the form of numerals rather than words and are usually rounded to two decimal places (e.g., “2.00” rather than “two” or “2”). They can be presented either in the narrative description of the results or parenthetically—much like reference citations. When you have a small number of results to report, it is often most efficient to write them out. Here are some examples:

- The mean age of the participants was 22.43 years with a standard deviation of 2.34.

- Among the participants with low self-esteem, those in a negative mood expressed stronger intentions to have unprotected sex (M= 4.05, SD = 2.32) than those in a positive mood (M = 2.15, SD = 2.27).

- The treatment group had a mean of 23.40 (SD= 9.33), while the control group had a mean of 20.87 (SD = 8.45).

- The test-retest correlation was .96.

- There was a moderate negative correlation between the alphabetical position of respondents’ last names and their response time (r= −.27).

Notice that when presented in the narrative, the terms mean and standard deviation are written out, but when presented parenthetically, the symbols M and SD are used instead. Also, notice that it is especially important to use parallel construction to express similar or comparable results in similar ways. The third example is much better than the following nonparallel alternative:

- The treatment group had a mean of 23.40 (SD= 9.33), while 20.87 was the mean of the control group, which had a standard deviation of 8.45.

Presenting Descriptive Statistics in Figures

When you have a large number of results to report, you can often do it more clearly and efficiently with a graphical depiction of the data, such as pie charts, bar graphs, or scatterplots. In an APA-style research report, these graphs are presented as figures.

When you prepare figures for an APA-style research report, there are some general guidelines that you should keep in mind. First, the figure should always add important information rather than repeat information that already appears in the text or in a table (if a figure presents information more clearly or efficiently, then you should keep the figure and eliminate the text or table.) Second, figures should be as simple as possible. For example, the APA (2020) Publication Manual discourages the use of colour unless it is absolutely necessary (although colour can still be an effective element in posters, slideshow presentations, or textbooks.) Third, figures should be interpretable on their own. A reader should be able to understand the basic result based only on the figure and its caption and should not have to refer to the text for an explanation.

There are also several more technical guidelines for presentation of figures that include the following (see the APA (2020) Publication Manual section 5.20 through 5.30):

- Layout of graphs

- In general, scatterplots, bar graphs, and line graphs should be slightly wider than they are tall.

- The independent variable should be plotted on the x-axis and the dependent variable on the y-axis.

- Values should increase from left to right on the x-axis and from bottom to top on the y-axis.

- The x-axis and y-axis should begin with the value zero.

- Axis labels and legends

- Axis labels should be clear and concise and include the units of measurement if they do not appear in the caption.

- Axis labels should be parallel to the axis.

- Legends should appear within the figure.

- Text should be in the same simple font throughout and no smaller than 8 pt and no larger than 14 pt.

- Captions

- Captions are titled with the word “Figure,” followed by the figure number in the order in which it appears in the text and terminated with a period. This title is italicized.

- After the title is a brief description of the figure terminated with a period (e.g., “Reaction times of the control versus experimental group.”)

- Following the description, include any information needed to interpret the figure, such as any abbreviations, units of measurement (if not in the axis label), units of error bars, etc.

Bar Graphs

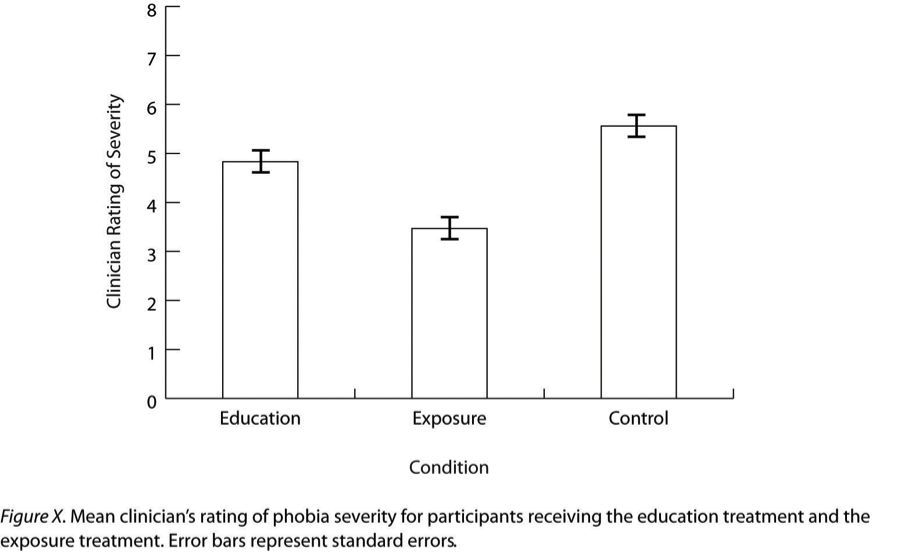

As we have seen throughout this book, bar graphs are generally used to present and compare the mean scores for two or more groups or conditions. The bar graph in Figure 9.7 is an APA-style version of Figure 9.7. Notice that it conforms to all the guidelines listed.

A new element in Figure 9.7 is the smaller vertical bars that extend both upward and downward from the top of each main bar. These are error bars, and they represent the variability in each group or condition. Although they sometimes extend one standard deviation in each direction, they are more likely to extend one standard error in each direction (as in Figure 9.7). The standard error is the standard deviation of the group divided by the square root of the sample size of the group. The standard error is used because, in general, a difference between group means that is greater than two standard errors is statistically significant. Thus, one can “see” whether a difference is statistically significant based on a bar graph with error bars.

Line Graphs

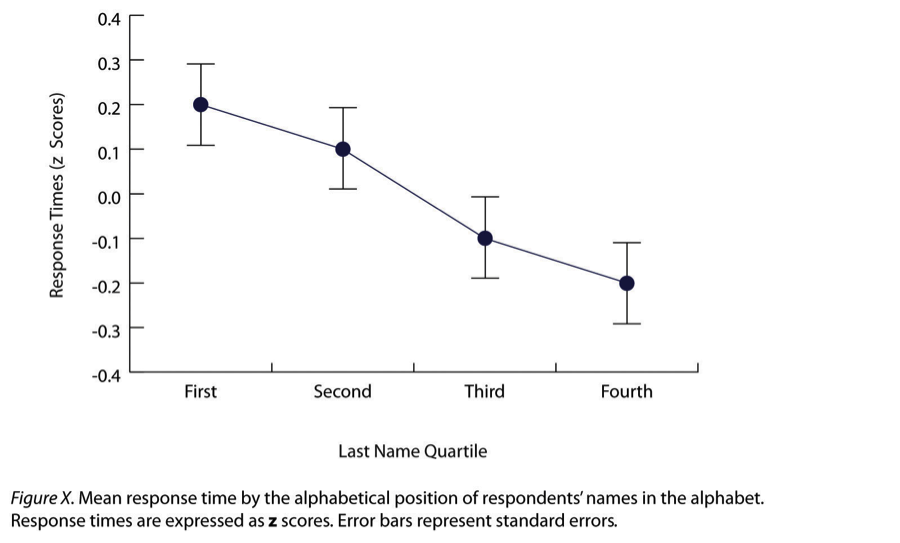

Line graphs are used when the independent variable is measured in a more continuous manner (e.g., time) or to present correlations between quantitative variables when the independent variable has, or is organized into, a relatively small number of distinct levels. Each point in a line graph represents the mean score on the dependent variable for participants at one level of the independent variable. Figure 7.8 is an APA-style version of the results of Carlson and Conard (2011). Notice that it includes error bars representing the standard error and conforms to all the stated guidelines.

In most cases, the information in a line graph could just as easily be presented in a bar graph. In Figure 9.8, for example, one could replace each point with a bar that reaches up to the same level and leave the error bars right where they are. This emphasizes the fundamental similarity of the two types of statistical relationships. Both are differences in the average score of one variable across the levels of another. The convention followed by most researchers, however, is to use a bar graph when the variable plotted on the x-axis is categorical and a line graph when it is quantitative.

Scatterplots

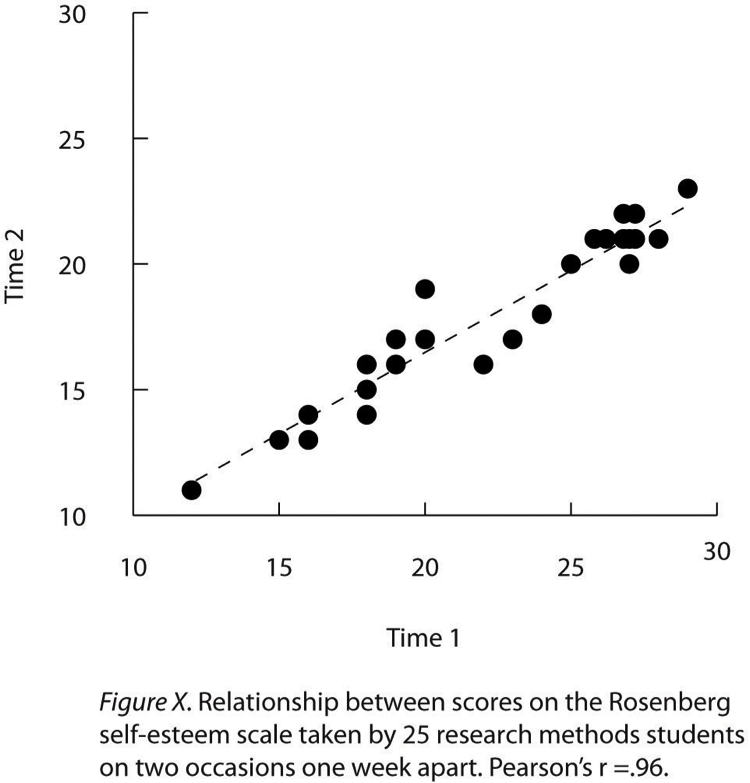

Scatterplots are used to present correlations and relationships between quantitative variables when the variable on the x-axis (typically the independent variable) has a large number of levels. Each point in a scatterplot represents an individual rather than the mean for a group of individuals, and there are no lines connecting the points.

The graph in Figure 9.9 illustrates a few points. First, when the variables on the x-axis and y-axis are conceptually similar and measured on the same scale—as here, where they are measures of the same variable on two different occasions—this can be emphasized by making the axes the same length. Second, when two or more individuals fall at exactly the same point on the graph, one way this can be indicated is by offsetting the points slightly along the x-axis. Other ways are by displaying the number of individuals in parentheses next to the point or by making the point larger or darker in proportion to the number of individuals. Finally, the straight line that best fits the points in the scatterplot, which is called the regression line, can also be included.

Expressing Descriptive Statistics in Tables

Like graphs, tables can be used to present large amounts of information clearly and efficiently. The same general principles that apply to tables also apply to graphs. They should add important information to the presentation of your results, be as simple as possible, and be interpretable on their own. Again, this section focuses on tables for an APA-style manuscript specifically.

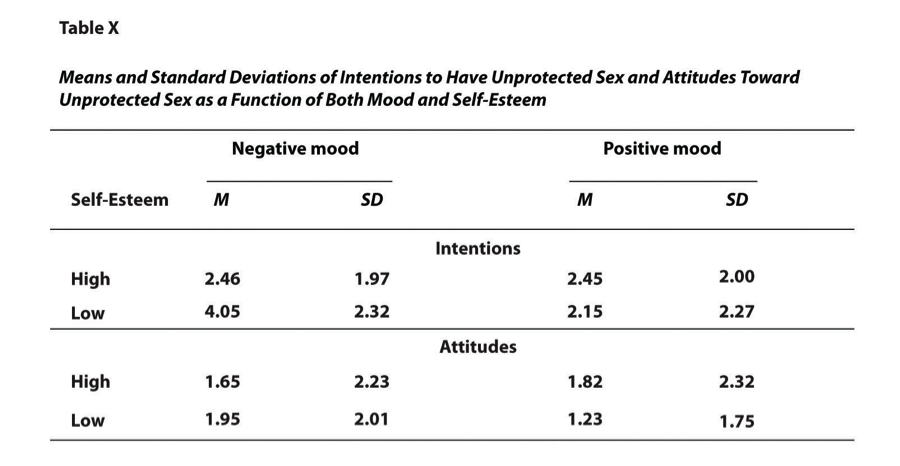

The most common use of tables is to present several means and standard deviations—usually for complex research designs with multiple independent and dependent variables. Figure 9.10, for example, shows the results of a hypothetical study similar to the one by MacDonald and Martineau (2002) (The means in Figure 9.10 are the means reported by MacDonald and Martineau, but the standard errors are not). Recall that these researchers categorized participants as having low or high self-esteem, put them into a negative or positive mood, and measured their intentions to have unprotected sex. They also measured participants’ attitudes toward unprotected sex.

Notice that the table includes horizontal lines spanning the entire table at the top and bottom, and just beneath the column headings. Furthermore, every column has a heading—including the leftmost column—and there are additional headings that span two or more columns that help to organize the information and present it more efficiently. Finally, notice that APA-style tables are numbered consecutively starting at 1 (Table 1, Table 2, and so on) and given a brief but clear and descriptive title.

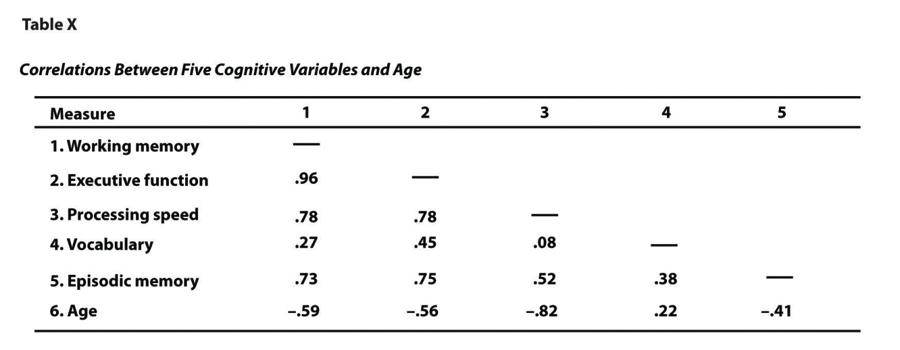

Another common use of tables is to present correlations—usually measured by Pearson’s r—among several variables. This kind of table is called a correlation matrix. Figure 9.11 is a correlation matrix based on a study by David McCabe and colleagues (2010). They were interested in the relationships between working memory and several other variables. We can see from the table that the correlation between working memory and executive function, for example, was an extremely strong .96, the correlation between working memory and vocabulary was a medium .27, and all the measures except vocabulary tend to decline with age.

Notice here that only half the table is filled in because the other half would have identical values. For example, the Pearson’s r value in the upper right corner (working memory and age) would be the same as the one in the lower left corner (age and working memory). The correlation of a variable with itself is always 1.00, so these values are replaced by dashes to make the table easier to read.

As with graphs, precise statistical results that appear in a table do not need to be repeated in the text. Instead, the writer can note major trends and alert the reader to details (e.g., specific correlations) that are of particular interest.

Manipulating Graphs

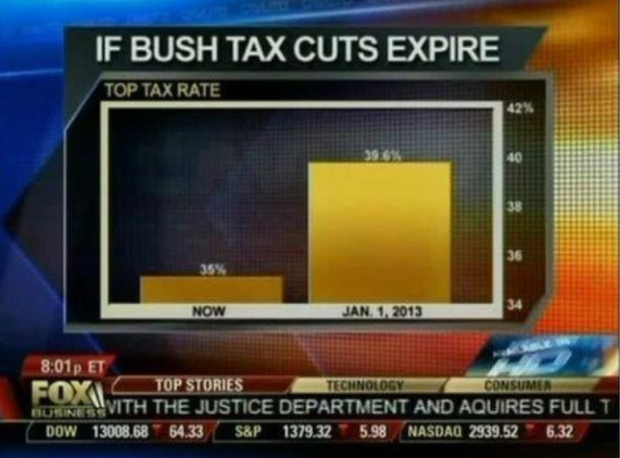

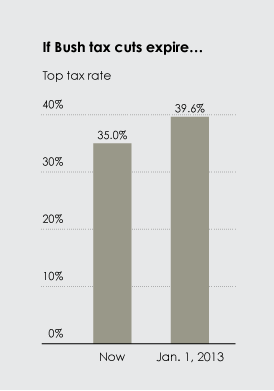

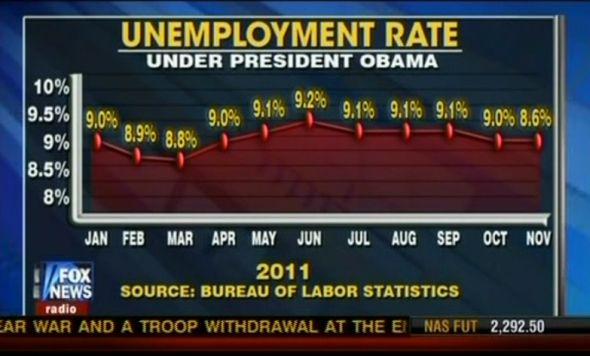

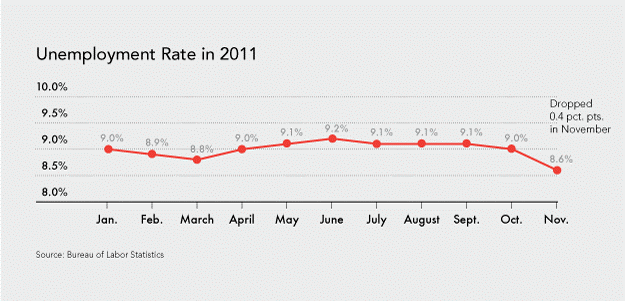

Manipulating graphs can mislead the audience and lead to false conclusions. While this could be done by mistake, this is often done deliberately to manipulate people towards a particular conclusion. Consider some of the following graphs from Fox News:

|

|

Figure 7.12 Bar graphs showing the effects of expiring Bush tax cuts as presented on Fox News and with proper ratios (Flowing Data, 2012)

In the above graph on the left, we see an actual bar graph broadcast by Fox News on the effects of the expiration of the Bush tax cuts under President Obama. At first glance, it looks like a five-fold increase in tax burden. However, we can see on the graph on the left that if you show the bar graph starting from zero, which shows a modest difference of 4.6%.

The above line graph is supposed to show the unemployment rate under president Obama. However, if we look carefully, we can see that the rises and drops in the graph have no relationship to the actual numbers. A drop from 9% to 8.6% in November is shown as a horizontal line (indicating no change) even though the rate in November is lower than the rate in March. The actual graph should look something like this:

These are just a few examples of how partisan media (such as Fox News) can manipulate data to reflect their own biases.

Media Attributions

- Figure 7.6 http://imgs.xkcd.com/comics/convincing.png (CC-BY-NC 2.5)

- Figure 7.7 Jhangiani, R.S., Chiang, I.A. Cuttler, C. & Leighton, D.C. (2019). Research Methods in Psychology, Surrey, Canada: Kwantlen Polytechnic University. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/HF7DQ

- Figure 7.8 Carlson, K. A., & Conard, J. M. (2011). The last name effect: How last name influences acquisition timing. Journal of Consumer Research, 38(2), 300–307. https://doi.org/10.1086/658470

- Figure 7.9 Jhangiani, R.S., Chiang, I.A. Cuttler, C. & Leighton, D.C. (2019). Research Methods in Psychology, Surrey, Canada: Kwantlen Polytechnic University. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/HF7DQ

- Figure 7.10 Jhangiani, R.S., Chiang, I.A. Cuttler, C. & Leighton, D.C. (2019). Research Methods in Psychology, Surrey, Canada: Kwantlen Polytechnic University. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/HF7DQ

- Figure 7.11 McCabe, D. P., Roediger, H. L., McDaniel, M. A., Balota, D. A., & Hambrick, D. Z. (2010). The relationship between working memory capacity and executive functioning: evidence for a common executive attention construct. Neuropsychology, 24(2), 222–243. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017619

- Figure 7.12 Flowing Data (August, 2012). Fox News continues charting excellence. FlowingData. https://flowingdata.com/2012/08/06/fox-news-continues-charting-excellence/

- Figure 7.13 Flowing Data (December, 2011). Fox News still makes awesome charts. FlowingData. https://flowingdata.com/2011/12/12/fox-news-still-makes-awesome-charts/

- Figure 7.14 Flowing Data (December, 2011). Fox News still makes awesome charts. FlowingData. https://flowingdata.com/2011/12/12/fox-news-still-makes-awesome-charts/