Solutions to the Problem

Dissemination of Replication Attempts

Here are some resources known for dissemination replication attempts:

- Psychfiledrawer.org: Archives attempted replications of specific studies and whether replication was achieved.

- Center for Open Science: Psychologist Brian Nosek, a champion of replication in psychology, has created the Open Science Framework, where replications can be reported.

- Association of Psychological Science: Has registered replications of studies, with the overall results published in Perspectives on Psychological Science.

- Plos One (Public Library of Science): Publishes a broad range of articles, including failed replications, and occasional summaries of replication attempts in specific areas.

- Replicability-Index: Created in 2014 by Ulrich Schimmack, the so-called “R-Index” is a statistical tool for estimating the replicability of studies, journals, and even specific researchers. Schimmack describes it as a “doping test”.

The fact that replications, including failed replication attempts, now have outlets where they can be communicated to other researchers is a very encouraging development and should strengthen the science considerably. One problem for many decades has been the near impossibility of publishing replication attempts, regardless of whether they were positive or negative.

The fact that replications, including failed replication attempts, now have outlets where they can be communicated to other researchers is a very encouraging development, and should strengthen the science considerably. One problem for many decades has been the near-impossibility of publishing replication attempts, regardless of whether they’ve been positive or negative.

The reward structure in academia has served to discourage replication. Many psychologists—especially those who work full-time at universities—are often rewarded at work—with promotions, pay raises, tenure, and prestige—through their research. Replications of one’s own earlier work, or the work of others, is typically discouraged because it does not represent original thinking. Instead, academics are rewarded for high numbers of publications, and flashy studies are often given prominence in media reports of published studies.

Psychological scientists need to carefully pursue programmatic research. Findings from a single study are rarely adequate and should be followed up by additional studies using varying methodologies. Thinking about research this way—as if it were a program rather than a single study—can help. We would recommend that laboratories conduct careful sets of interlocking studies, where important findings are followed up using various methods. It is not sufficient to find some surprising outcome, report it, and then move on. When findings are important enough to be published, they are often important enough to prompt further, more conclusive research. In this way, scientists will discover whether their findings are replicable and how broadly generalizable they are. If the findings do not always replicate, but do sometimes, we will learn the conditions in which the pattern does or does not hold up. This is an important part of science—to discover how generalizable the findings are.

When researchers criticize others for being unable to replicate the original findings—saying that the conditions in the follow-up study were changed—is important to pay attention to, as well. Not all criticism is knee-jerk defensiveness or resentment. The replication crisis has stirred heated emotions among research psychologists and the public, but it is time for us to calm down and return to a more scientific attitude and system of programmatic research.

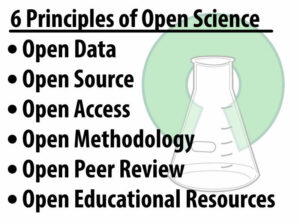

Open Science Practices

It is important to shed light on questionable research practices to ensure that current and future researchers (such as yourself) understand the damage they wreak to the integrity and reputation of our discipline (see, for example, the “Replicability-Index,” a statistical “doping test” developed by Ulrich Schimmack in 2014 for estimating the replicability of studies, journals, and even specific researchers). However, in addition to highlighting what not to do, this so-called “crisis” has also highlighted the importance of enhancing scientific rigour by:

- Designing and conducting studies that have sufficient statistical power in order to increase the reliability of findings.

- Publishing both null and significant findings (thereby counteracting the publication bias and reducing the file drawer problem).

- Describing one’s research designs in sufficient detail to enable other researchers to replicate the study using an identical or at least very similar procedure.

- Conducting high-quality replications and publishing these results. (Brandt et al., 2014)

One particularly promising response to the replicability crisis has been the emergence of open science practices that increase the transparency and openness of the scientific enterprise. For example, Psychological Science (the flagship journal of the Association for Psychological Science) and other journals now issue digital badges to researchers who pre-registered their hypotheses and data analysis plans, openly shared their research materials with other researchers (e.g., to enable attempts at replication), or made their raw data available to other researchers (see Figure 10.2).

These initiatives, which have been spearheaded by the Center for Open Science, have led to the development of “Transparency and Openness Promotion guidelines” (see Table 10.2) that have since been formally adopted by more than 500 journals and 50 organizations, a list that grows each week (Nosek et al., 2015). When you add to this the requirements recently imposed by federal funding agencies in Canada (the Tri-Council) and the United States (National Science Foundation) concerning the publication of publicly-funded research in open access journals, it certainly appears that the future of science and psychology will be one that embraces greater “openness.”

| Criteria | Level 0 | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citation standards | Journal encourages citation of data, code, and materials, or says nothing | Journal describes citation of data in guidelines to authors with clear rules and examples. | Article provides appropriate citation for data and materials used consistent with journal’s author guidelines. | Article is not published until providing appropriate citation for data and materials following journal’s author guidelines. |

| Data transparency | Journal encourages data sharing, or says nothing | Article states whether data are available, and, if so, where to access them. | Data must be posted to a trusted repository. Exceptions must be identified at article submission. | Data must be posted to a trusted repository, and reported analyses will be reproduced independently prior to publication. |

| Analytic methods (Code) transparency | Journal encourages code sharing, or says nothing | Article states whether code is available, and, if so, where to access them. | Code must be posted to a trusted repository. Exceptions must be identified at article submission. | Code must be posted to a trusted repository, and reported analyses will be reproduced independently prior to publication. |

| Research materials transparency | Journal encourages materials sharing, or says nothing | Article states whether materials are available, and, if so, where to access them. | Materials must be posted to a trusted repository. Exceptions must be identified at article submission. | Materials must be posted to a trusted repository, and reported analyses will be reproduced independently prior to publication. |

| Design and analysis transparency | Journal encourages design and analysis transparency, or says nothing | Journal articulates design transparency standards | Journal requires adherence to design transparency standards for review and publication | Journal requires and enforces adherence to design transparency standards for review and publication |

| Preregistration of studies | Journal says nothing | Journal encourages preregistration of studies and provides link in article to preregistration if it exists | Journal encourages preregistration of studies and provides link in article and certification of meeting preregistration badge requirements | Journal requires preregistration of studies and provides link and badge in article to meeting requirements. |

| Preregistration of analysis plans | Journal says nothing | Journal encourages pre-analysis plans and provides link in article to registered analysis plan if it exists | Journal encourages pre-analysis plans and provides link in article and certification of meeting registered analysis plan badge requirements | Journal requires preregistration of studies with analysis plans and provides link and badge in article to meeting requirements. |

| Replication | Journal discourages submission of replication studies, or says nothing | Journal encourages submission of replication studies | Journal encourages submission of replication studies and conducts results blind review | Journal uses Registered Reports as a submission option for replication studies with peer review prior to observing the study outcomes. |

Note. Table reproduced with permission from Center for Open Science (Nosek et al., 2015)

Textbooks and Journals

Some psychologists blame the trend toward non-replication on specific journal policies, such as the policy of Psychological Science to publish short single studies. When single studies are published, we do not know whether even the authors themselves can replicate their findings. The journal Psychological Science has come under perhaps the harshest criticism. Others blame the rash of nonreplicable studies on a tendency of some fields for surprising and counterintuitive findings that grab the public interest. The irony here is that such counterintuitive findings are, in fact, less likely to be true precisely because they are so strange—so they should perhaps warrant more scrutiny and further analysis.

The criticism of journals extends to textbooks, as well. In our opinion, psychology textbooks should stress true science, based on findings that have been demonstrated to be replicable. There are a number of inaccuracies that persist across common psychology textbooks, including small mistakes in common coverage of the most famous studies, such as the Stanford Prison Experiment (Griggs & Whitehead, 2014) and the Milgram studies (Griggs & Whitehead, 2015). To some extent, the inclusion of non-replicated studies in textbooks is the product of market forces. Textbook publishers are under pressure to release new editions of their books, often far more frequently than advances in psychological science truly justify. As a result, there is pressure to include “sexier” topics such as controversial studies.

Ultimately, people also need to learn to be intelligent consumers of science. Instead of getting overly excited by findings from a single study, it is wise to wait for replications. When a corpus of studies is built on a phenomenon, we can begin to trust the findings. Journalists must also be educated about this and learn not to readily broadcast and promote findings from single flashy studies. If the results of a study seem too good to be true, maybe they are. Everyone needs to take a more skeptical view of scientific findings, until they have been replicated.

Media Attributions

- Figure 8.1 openscienceASAP. Underlying Image: CC by-SA 3.0; Greg Emmerich)

- Figure 8.2 Center for open Science